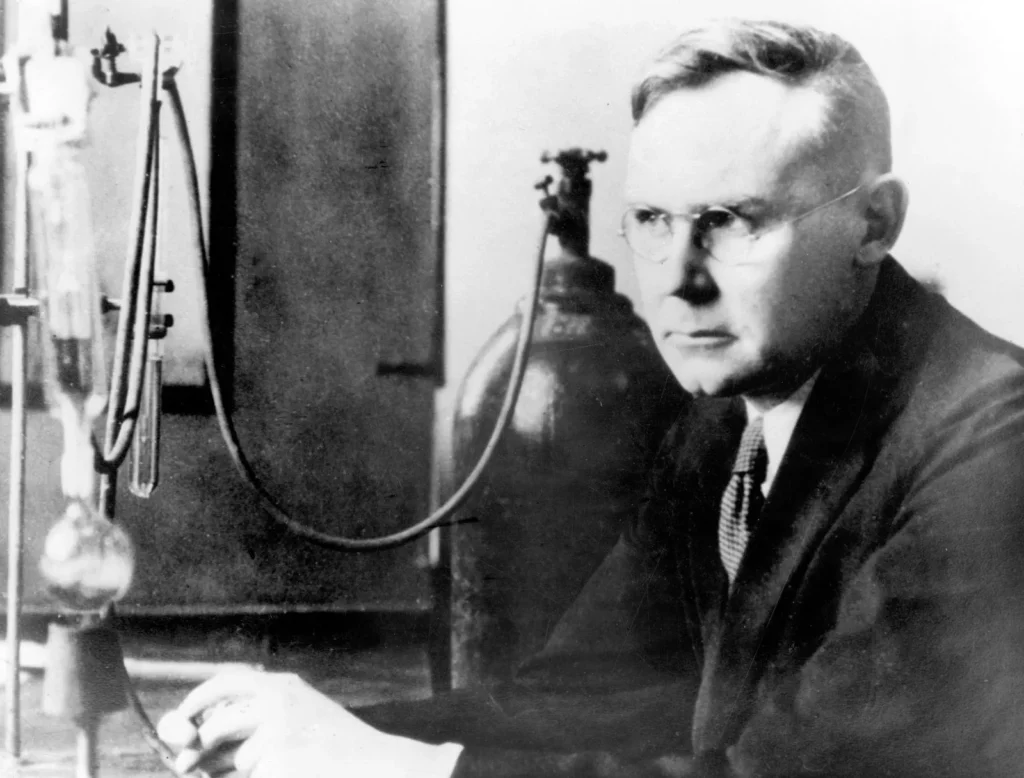

Wallace Carothers

Wallace Hume Carothers (/kəˈrʌðərz/; April 27, 1896 – April 29, 1937) was an American chemist, inventor and the leader of organic chemistry at DuPont, who was credited with the invention of nylon.

Carothers had been troubled by periods of depression since his youth. Despite his success with nylon, he felt that he had not accomplished much and had run out of ideas. His unhappiness was exacerbated by the death of his sister, and on April 28, 1937, he committed suicide by drinking potassium cyanide.

There’s a fine line between genius and insanity.

Oscar Levant

The link between mental illness and genius is connection well-known to some of history’s greatest minds. Vincent Van Gogh, Ernest Hemingway, Ludwig Boltzmann, and Sylvia Plath are just a few of society’s greatest thinkers who suffered from chronic mental illness. Furthermore, all of them wound up tragically taking their own lives as a result.

Oscar Levant himself, who many considered a multi-faceted genius, spoke openly and frequently about his neuroses and hypochondria. The quote above concludes thusly: “I have erased this line.”

Such is the case with Wallace Hume Carothers, the inventor of Nylon who singlehandedly transformed the field of synthetic polymers in the early 20th century. Carothers was undoubtedly one of history’s greatest chemists. His supervisor Elmer Bolton once descrbied him as “…one of the most brilliant organic chemists ever employed by the DuPont company.” His invention of Nylon revolutionized the textile industry and many others.

And yet, Carothers would not live to see the tremendous impact of his life’s work. Plagued by depression his entire life, Carothers was perpetually haunted by the fear that he would never achieve anything of real significance – a feeling one might these days call “imposter syndrome”. His depression eventually led him to suicide in 1937 at the young age of 41, roughly two years before his creation became an international best-seller.

That such an outstanding man with so many achievements to his name became depressed and suicidal speaks volumes about the power of mental illness and overwhelming burden of high achievement.

Young Brilliance

Born in Burlington, Iowa in 1896, Wallace Hume Carothers showed early signs of exceptional intelligence:

As a youth, Carothers was fascinated by tools and mechanical devices and spent many hours experimenting. He attended public school in Des Moines, Iowa, where he was known as a conscientious student.

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Education and academic career

Carothers, however, was admittedly prone to indecisiveness. He often found choosing a definitive life direction difficult. Under pressure from his father, Carothers enrolled in the Capital City Commercial College in Des Moines, where his father was vice-president.

Carothers relented, though it is uncertain if he was happy with this forced decision. We can only speculate that this early pressure from his father might have formed the basis of his insecurities and his eventual proclivity of prioritizing success before his own happiness.

Regardless, he graduated from Capital City Commercial College in July 1915 and entered Tarkio College in Missouri two months later. He initially studied English before switching to chemistry.

It was here that Carothers began to exhibit his relentless drive that would come to define his later years. He excelled in all of his classes, quickly outdistancing himself from his classmates. During his senior year, he was made chemistry instructor of a class he himself was taking. The stress must have been tough to endure: Before he graduated, Carothers had become a smoker.

Carothers would go on to attain several appointments at various universities before receiving his Ph.D. at the University of Illinois. There he received the Carr Fellowship for 1923-24, the university’s most prestigious award at the time.

Carothers eventually became an instructor in organic chemistry at Harvard University in 1926.

He continued to distinguish himself there, and the future president of the college would later remark:

In his research, Dr. Carothers showed even at this time the high degree of originality which marked his later work. He was never content to follow the beaten path or to accept the usual interpretations of organic reactions. His first thinking about polymerization and the structure of substances of high molecular weight began while he was at Harvard.

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Education and academic career

Mental Illness Sets In

Carothers, however, was a man plainly marked by what we would now recognize as chronic depression.

By the time Carothers had made the decision to leave Harvard in 1928 to pursue a career at DuPont’s new laboratory for fundamental research (dubbed “the Experimental Station”), his depression was readily apparent.

Carothers refused DuPont’s initial offer, ostensibly self-aware of his emotional instability and worried that it would not be tolerated outside of a cushy academic role:

The decision to leave academia was difficult for Carothers. At first he refused DuPont’s offer of employment, explaining that “I suffer from neurotic spells of diminished capacity which might constitute a much more serious handicap there than here.

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Move to DuPont

However, he was eventually wooed by a DuPont executive, who promised him a lavish salary, a well-furnished lab, and full control over his own research.

Despite this impressive milestone, Carothers continued to feel numbed by his depression. In a later letter to his college roommate, he elaborates upon his feelings of worthlessness and his accompanying lack of emotion:

I find myself, even now, accepting incalculable benefits proffered out of sheer magnanimity and good will and failing to make even such trivial return as circumstances permit and human feeling and decency demand, out of obtuseness or fear or selfishness or mere indifference and complete lack of feeling.

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Move to DuPont

Nevertheless, DuPont would ultimately become the launch pad for some of Carothers’ greatest discoveries, and all his efforts were soon met with great success. By 1930, his research into an acetylene polymer had produced the world’s first synthetic rubber, which is today known as Neoprene. He also helped create the first synthetic silk. His research led him to work out the theory of step-growth polymerization and derived the Carothers equation of polymerization.

His growing list of accomplishments earned him renown in the scientific community. Although shy of public speaking, he was frequently invited to symposiums where he spoke about his research at DuPont.

Downward Spiral

Carothers’ depression was a lifelong struggle, as is often the case with many of those who suffer from it. From 1931 onward, however, Carothers would show more frequent signs of a spiraling mood. Increasing pressure at DuPont to produce a commercially viable polymer weighed down upon him heavily.

Carothers documented his persistent anhedonia in a letter to a friend:

He was no recluse, but his depressive moods often prevented him from enjoying all the activities in which his roommates took part. In a letter to a close friend, Frances Spencer, he said, “There doesn’t seem to be much to report concerning my experiences outside of chemistry. I’m living out in the country now with three other bachelors, and they being socially inclined have all gone out in tall hats and white ties, while I after my ancient custom sit sullenly at home.”‘

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Later career and depression

Carothers also kept a capsule of cyanide attached to his watch chain, a dire warning of things to come. He apparently showed it to fellow alumnus Julian Hill around this time, though no mention is made of how he might have reacted to this alarming revelation.

Failing to find relief from his condition, Carothers turned more frequently to alcohol to self-medicate, a habit which had apparently taken hold of him towards the end of college:

In a letter to Frances Spencer in January 1932, he related, “I did go up to New Haven during the holidays and made a speech at the organic symposium. It was pretty well received but the prospect of having to make it ruined the preceding weeks and it was necessary to resort to considerable amounts of alcohol to quiet my nerves for the occasion.”

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Later career and depression

Alcohol’s comforts, however, always proved temporary, and it’s possible Carothers’ drinking exacerbated his emotional problems during his later years. Carothers ends his letter on a dismal note:

“My nervousness, moroseness and vacillation get worse as time goes on, and the frequent resort to drinking doesn’t bring about any permanent improvement. 1932 looks pretty black to me just now.”

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Later career and depression

Compounding his emotional issues was the added stress of looking after his parent’s financial issues. To stifle his worries, he impulsively bought a house near his work in Delaware and had his parents move in with him so that they would be close by.

His parents soon uncovered an affair Carothers (then unmarried) was having with a married woman named Sylvia Moore, who was still in the process of divorcing her husband. Word got out. His parents, coworkers, and bosses disapproved heavily. Tensions flared. His parents eventually had enough of it and moved out the next year. It’s easy to imagine that the judgement of his parents and coworkers only pushed Carothers deeper into depression.

The Invention of Nylon

Nonetheless, Carothers’ professional life flourished. He was hailed as a brilliant chemist by his peers and supervisors, and DuPont continued to push him on towards new research. His work resulted in the invention of a number of new polyamides, a type of synthetic polymer.

During this highly productive period, however, Carothers’ began the first of his sudden and prolonged absences from work:

It was… in the summer of 1934, before the eventual invention of nylon, that Carothers disappeared. He did not come into work, and no one knew where he was. He was found in a small psychiatric clinic, Pinel Clinic, near the famous Phipps Clinic associated with Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Apparently, he had become so depressed that he drove to Baltimore to consult a psychiatrist, who put him in the clinic.

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Polyamides

Carothers’ greatest achievement, however, still lay ahead of him. Upon his return to work, DuPont instructed Carothers to continue his work on polyamides. The fruit of his labors was the creation of Nylon in early 1935, a product which Carothers is directly credited with inventing.

Nylon would become a scientific and commercial breakthrough: It was the first synthetic polymer fiber to see commercial production and laid the groundwork for the synthetic fiber industry.

It’s popularity exploded during WWII with the invention of Nylon stockings. Sales of stockings eventually ceased when all Nylon production was diverted towards making parachutes and other materials for the army. When Nylon stockings returned to the market following the end the war, initial demand was so steep that shortages actually caused “nylon riots” inside of stores.

The End of Carothers

Carothers’ many contributions to chemistry continued to earn him praise. In 1936, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, becoming the first industrial organic chemist to receive this extraordinary honor. After breaking off his previous affair, he married Helen Sweetman (who also worked at DuPont) that same year. They were soon after expecting their first child.

Yet despite his many accolades and unrivaled creative output, Carothers continued to believe that he had exhausted all of his scientific potential. By June 1936, Carothers’ depression began to cripple his ability to work:

In early June, he was involuntarily admitted to the Philadelphia Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, a prestigious mental hospital, where his psychiatrist was Dr. Kenneth Appel.

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Marriage and death

A month later in July, he disappeared once again while out on an extended hike in the Alps, this time for two whole months:

One month later, he was given permission to leave the institute to go hiking in the Tyrollean Alps with friends. The plan was for him to day hike with Dr. Roger Adams and Dr. John Flack for two weeks. After they left, he stayed on, hiking by himself, without sending word to anyone, even his wife. On September 14, he suddenly appeared at her desk at the Experimental Station.

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Marriage and death

By this time, Carothers’ peers could no longer ignore his grim disposition. Despite his erratic absences from work, Carothers was still highly regarded at DuPont, and so he was simply permitted to come and go as he pleased without risk to his employment. His wife stopped living with him on the advice of his psychiatrist:

From that point on Carothers was not expected to perform any real work at the Experimental Station. He would often go in and visit. He began living in Whiskey Acres again, after his wife had agreed with Dr. Appel that she was not strong enough to watch over Carothers.

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Marriage and death

The death of Carothers’ sister Isobel from pneumonia in January 1937 appeared to be the final straw. Following the funeral, Carothers traveled to Philadelphia to visit Dr. Appel, his psychiatrist, who foresaw the obvious outcome:

He still traveled to Philadelphia to visit his psychiatrist, Dr. Appel, who told a friend of Carothers that he thought suicide was the likely outcome of Carothers’ case.

Wikipedia, Wallace Carothers – Marriage and death

On April 28, 1937, Carothers went in to work at DuPont. The next day, two days after his 41st birthday, he committed suicide in a hotel room in Philadelphia. He used a cocktail of cyanide and lemonade, knowing from his chemical expertise that the acidic lemon juice would intensify the cyanide’s effects. He left no note. His daughter was born seven months later.

Legacy & Aftermath

Carothers lived his life in profound fear that he would never contribute anything important to society. It is a bitter irony that had he lived for just 16 more months, he would have witnessed the magnitude of his life’s work. Nylon production went into full effect in 1939 and became an immediate best-seller. It has gone on to find widespread use in the textile, automobile, manufacturing, and food packaging industries, amongst many others.

In addition to his inventions, Carothers published dozens of papers over the course of his career that essentially laid the foundation for the study and understanding of polymers. His contributions to the field cannot be understated. He is, in many regards, the father of polymer science. The Carothers Research Laboratory at DuPont was dedicated in his honor on September 17, 1946.

What can be learned from the life of Wallace Hume Carothers? If anything, it’s that Carothers’ struggle with depression should serve as a cautionary tale to those who underestimate the terrible power of mental illness. Despite heaps of external validation and awards, Carothers was never able to free himself from his deep feelings of inadequacy brought about by his depression.

But perhaps another lesson to be gleaned is that professional success alone does not guarantee happiness. Carothers was hounded by the anxiety that he would never be good enough, and yet his endless list of scientific accomplishments was unable to satisfy his unmet cravings for fulfillment. His relentless push towards success likely contributed to his mental decline. Achievement alone cannot sustain a life.

One wonders how Carothers’ life could have turned out had he access to the modern miracles of anti-depressants and psychotherapy. As it was, Carothers was a man in need of help far before society would come to understand the sickness that took his life.

Leave a Reply